The Epicene's Smörgåsbord

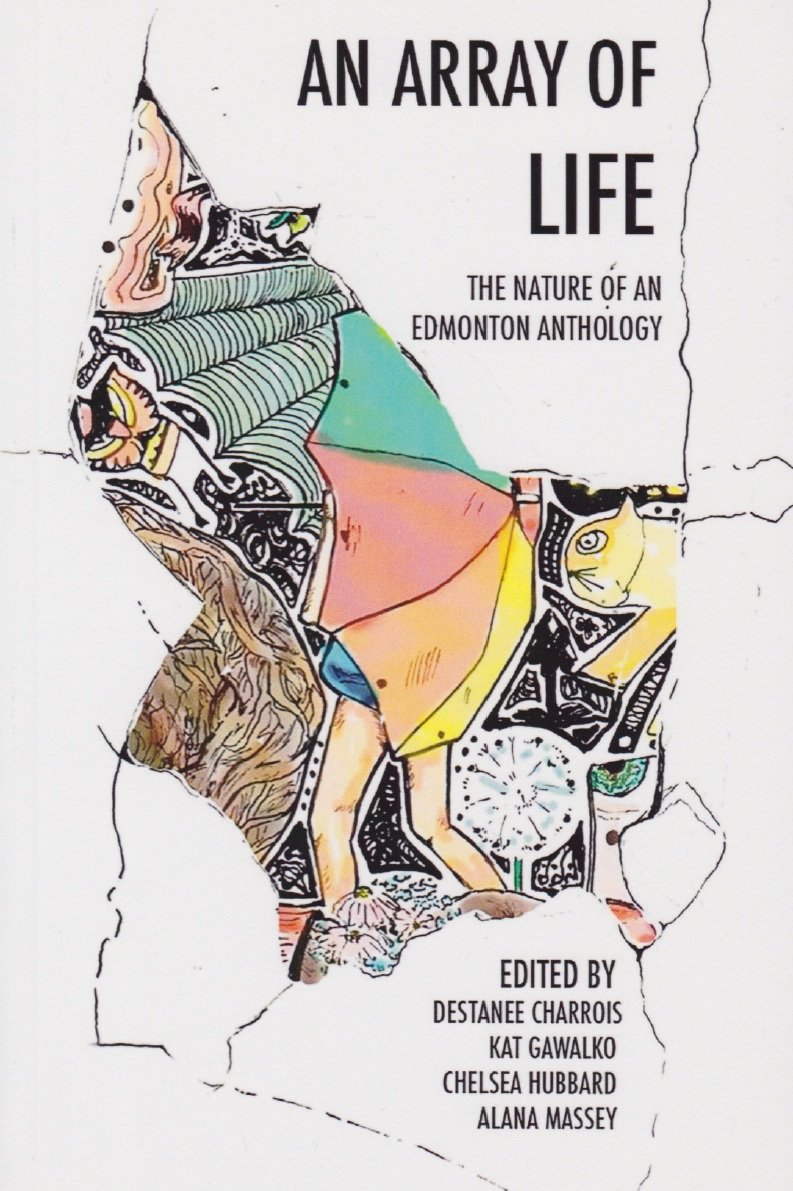

I wrote this short story for An Array of Life: The Nature of an Edmonton Anthology (2015).

The story takes place in a parallel-universe Edmonton where a trio of unlikely friends - a celebrity fleeing their gilded cage, a young fat girl fleeing bullies, and a university professor who only speaks in quotes - go on a fantastical urban adventure.

The Epicene’s Smörgåsbord

It’s warmed up this past month. No more vicious wind which licks like whips at exposed skin. No more dawns at 10:00 and dusks at 4:00 and empty eternities of soul-eroding night. Instead we have sunlight that beats down on the city, turning ice-clogged roads into rivers of meltwater. Instead we have air that doesn’t flay your nostrils for daring to inhale, but carries a rich bouquet of warm, loamy odours. Especially here.

I’m crouched inside a dumpster behind a Greek restaurant with an elderly Chinese-Canadian woman in downtown Edmonton.

I pick up a granola bar wrapper covered with almond butter and give it to my friend, whose mouldering business cards identify her as Professor Tammy Chang, Department of English.

“To eat is a necessity,” she says, licking the wrapper clean, “but to eat intelligently is an art.”

She passes me a half-chewed pear, which still tastes sweet and firm. I rustle around and find a piece of baklava stuck to a paper napkin.

Our midday meal has become a ritual of exchanges. At first, when I started wandering the streets aimlessly and came upon this stooped old lady, we were both very cautious. But over the past month we’ve grown used to each other, sharing this new home.

It’s very different than any of the homes I’ve had before. Gritty. Exposed brick. Open-concept. Subway bread smell drifts up the alley from the fast-food outlet at its mouth. Frank Sinatra croons “My Way” from the speakers of a nearby café. Graffiti adorns the rough walls, declaring such things as “Flames Suck” and “Down with Baby Trudeau,” alongside a weatherworn “Eaton’s Groceteria” advertisement.

I’m about to resume the Rites of Lunch when a fat white girl in a bright pink winter coat charges into our alley, pursued by a pack of boys. She’s about twelve years old, has a maroon backpack bouncing below her cascading ginger hair, and she’s wearing clunky rubber boots which are much too big for her.

I register the panic in her eyes as they lock onto mine and then boom she’s down, tripping belly-first into a slush-filled pothole. The boys cackle and race towards her.

Without thinking I leap out of the dumpster. I draw myself up to my maximum height—which is not a considerable altitude—hook my fingers through my belt loops, and suddenly I’m an Old West sheriff, ready to lay down the law. I stride past the girl, and I can practically hear the spurs on my cowboy boots jangling. I plant myself in front of her, legs spread, wide-brimmed hat shielding my eyes from the desert sun. The boys scramble to a halt, unsure of this development.

The leader of the pack lets his eyes rove over my body, peeling away the layers of my newly constructed self-image. I snap it back in place and drawl out at them:

“Y’all better clear out now, ya hear? Don’t wanna be gettin’ yourselves into no trouble.”

The boys all look to their leader, waiting to follow his cue. I take a step forward, shifting my hand to my hip, fingers hovering over my holster.

“What part of ‘git’ don’t you boys understand? This here’s MY TOWN, and we don’t stand for no hoodlums!”

I advance on them, and the boys are spooked. They start inching away, not wanting to wimp out but not willing to get their soft little asses kicked in. The leader notices this and tries to regain control of the scene. He forces a laugh.

“C’mon guys, we’ve got better things to do than talk to street bums.” He looks past me at the girl, who’s dripping with muck and glaring at him. “Have fun with your new friend, fat ass!”

The boys strut off down the alley, playing it cool. They glance back as they turn the corner onto the street. The leader gives us the middle finger and his cronies gasp and laugh.

I turn to the girl. She looks at me warily.

“Y’alright?”

I hear the sheriff lingering in my voice and cough it out.

“Sorry. Are you okay?”

She looks me up and down and frowns. I know she’s asking herself the same question that everyone asks these days. The question that I fought for so long to keep out of people’s minds, until I realized that I enjoyed having it there. That it made me powerful. That it allowed me to experience things most people don’t allow themselves to experience.

“Are you a man or a woman?”

I hold her gaze for a moment, then slowly shake my head.

“No.”

Over the past month I’ve revolted against my anxieties and embraced the ambiguity of my body. I let my hair go wild and it grew with impossible speed. Now it hangs around my shoulders. I’ve taken to wearing black, form-fitting clothing that emphasizes certain curves and invents others. When people look at me they frown, and ask themselves the question that I now encourage. Especially white people, who often have difficulty gendering people of colour. And I am brown as the mouths of rivers.

I’ve found this absence-of-gender to be very useful; I can overlay anything I want onto it, for any context. I imagine myself into a character, and act with the full force and confidence of that new personality. For example, a badass sheriff chasing off some bandits.

I ruffle my feathers and become a fairy godmother, to comfort and delight. The girl’s eyes widen at my transformation.

“I used to be a man,” I say, leaning back against the dumpster. “Not much of a man, I grant you. I was always too short, too skinny. I couldn’t grow a beard. I kept my hair cropped close to my skull so nobody would accidentally ‘ma’am’ me from behind.”

I run my fingers through my bedraggled mane and sigh.

“But I got tired of it. Being a man is so much work. You have to shut down whole parts of yourself, monitor what you’re doing just in case it’s not a manly thing to do. Don’t admit to knowing anything about cosmetics or fashion. Be disgusted by the details of female bodies, even as you crave ownership over them. Don’t cry, don’t show emotions, don’t even admit to having them.”

Rush hour traffic grumbles past the alley’s mouth. Brisk businesspeople march past, never casting a sideways glance at us. The panting, slush-drenched girl has eyes only for me.

“It was like I lived in a grand palace, but I only ever let myself go into three or four rooms. And I want to visit all the rooms. The study and the nursery, the garage and the kitchen and the library. And to do that, I had to stop thinking about walls entirely.”

“All boundaries are conventions, waiting to be transcended,” says Professor Tammy, popping her head over the lip of the dumpster.

The girl jumps in surprise.

“Oh yes, this is my best friend Professor Tammy Chang. This is…”

“Diana,” says the girl hesitantly. She brushes slush off her coat. It’s dirty, but drying fast in the sun. Her face is flushed and sweaty.

Professor Tammy grins at her, and I take her mittened hand in mine.

“I’m very pleased to meet you, Diana. I don’t have a name right now, or else I’d introduce myself.”

Diana’s eyes narrow.

“What do you mean you don’t have a name? Of course you do.”

“Sometimes it’s bad to have a name. Sometimes a name is just a beam from which to hang a noose.”

Diana stares into my eyes in an unsettling way. There’s something about her intense gaze that boils off all my illusions. I can feel the fairy godmother evaporating from my skin.

I flit away from the dumpster and pirouette around Diana, escaping her gaze and smiling to myself at the feeling of this new mystique.

“No single name could ever capture my infinite variety.”

“Other women cloy the appetites they feed, but she makes hungry where most she satisfies,” murmurs Professor Tammy, sinking back into the dumpster.

“So… you want to be a woman now?” asks Diana. “Is that what all this has been about?”

“I could be a woman or a man, or something in between, or something totally different.”

“Thesis, antithesis, synthesis,” Professor Tammy intones, her voice resonating out from the dumpster.

“I move through space and time, and I change forms. I can’t think of myself as just ‘a man’ anymore. That’s a lie.”

“Unity. Plurality. Totality.” Professor Tammy chants.

“It’s like when you see a two-dimensional representation of a cube, and you don’t know which way the cube really sits, and your mind flips back and forth between multiple interpretations.”

“A Necker Cube,” says Diana.

“What’s that?”

“That’s exactly what you’re describing. It’s an optical illusion that Louis Albert Necker invented in 1832. I read about it on Wikipedia…”

“Yes that’s it exactly. I’m like a Necker cube—a three-dimensional object in a two-dimensional context.”

I smile at her, impressed. “You’re really smart.”

She shrugs. “I read a lot. I have a lot of time because I have no friends.”

She glances back towards the alley’s mouth.

“Why were they chasing you?”

She gives me a sour scowl.

“Are you stupid? Look at me.”

Her voice is hard. She’s had enough of people pitying her, pretending that they’re too righteous to have noticed her body is different, is less than ideal.

“Well they won’t be coming back around here any time soon,” I say.

“Oh yes they will,” she says. “They’re like hyenas—”

“They scare easily but they'll be back, and in greater numbers,” says Professor Tammy, clambering out of the dumpster.

“Exactly,” says Diana.

“Well we better make ourselves scarce then,” I say. I go over to our pile of ratty blankets beside the dumpster, grab the big rectangular bag into which I’ve stuffed my new life, and drag it out into the centre of the alleyway. I lift the top flap and grin up at Diana.

“It’s good to have props and costumes before you go out and face the world,” I say. “Then people will take your self-image more seriously. They can always see it when you act it, but a little help never hurts.”

“The apparel oft proclaims the man,” says Professor Tammy, selecting a clip-on bowtie from my tickle trunk. “Naked people have little or no influence on society.”

She shuffles over to her favourite piece of cardboard.

Diana looks apprehensively at the nest of blankets, the magazine cut-outs stuck to the walls around Professor Tammy’s den, the mouldy pile of books next to her bed.

“So you really are street bums…”

Professor Tammy scoffs, and leans back against her oil drums luxuriously. “I choose to live my life on my own terms, and in surroundings with which I can identify. That is the privilege of wealth.” She adjusts the tattered old Oilers jersey she’s wearing with dignity.

“Come on Diana,” I entice. “Take a mask. Come on an adventure with us.”

Diana hesitates, then leans over and starts rooting around for a costume.

“This bag really smells,” she says.

“Yeah, it used to hold a bunch of sweaty stuff… never mind. Take anything you want.”

She selects an enormous pair of sunglasses. I take out a tiara and a sparkling wand.

“Now,” I say, “if I could grant you one wish, what would it be?”

“I don’t know,” says Diana.

“Of course you do. Just tell me.”

I swish and flick my wand back and forth, waiting patiently. Diana watches me for several moments, weighing whether or not if she’ll indulge me. She crosses her arms.

“Not that it matters, but if I could really have any wish, I would wish to get out of here. Not just this alley I mean, but get out of Edmonton.”

“And where would you go?”

“Phoenix,” she says immediately.

“Why Phoenix?”

She shakes her head.

“Nevermind. No reason. Forget I mentioned it.”

Suddenly she seems agitated. She takes off the sunglasses and sets them back in the bag.

“I should probably get going,” she says.

“We should all get going,” I say. “We should fly to Phoenix, and quickly.”

Diana rolls her eyes.

“Look, thank you for helping me get away from Brendan and them. But I really need to go. Not to Phoenix, just home.”

“What’s so great at home?” I ask.

“Don’t tell me not to fly,” says Professor Tammy, “I simply got to.”

“Professor Tammy is right,” I say. “If ever you’re unhappy with things, one of the best solutions is to seek green pastures elsewhere. You can become a new person in a new context.”

Diana looks around at the melting alleyway, then shakes her head.

“We can’t go to Phoenix,” she says. “We don’t have passports or any money.”

“Well fine, but least come with us on a little adventure and we’ll see where we end up”

Diana scrutinizes me with that laser-sharp intensity, then finally nods.

“Fine,” she says. “I’ve nothing better to do.”

“The world is not yet exhausted,” says Professor Tammy, sweeping her arms around us. “Let me see something tomorrow which I never saw before.”

* * *

When on an urban odyssey, meanders are not only enjoyable, but necessary. As the sun fades out and the streets clear of commuters, we tramp around downtown. We soak our feet at the base of the Citadel’s indoor waterfall, and warm our hands at the bonfire in front of city hall. We walk past the mangled silver ruins of the art gallery, which was dynamited by art terrorists a year ago and still hasn’t been fully cleaned up. We wander past the Harbin Gate, beg some fortune cookies off a tough old restauranteur, and we all swap fortunes when we find we like each other’s more than our own.

“We could go by Katz Place,” says Diana.

“I try to avoid the arena,” I say. “I don’t like that neighbourhood.”

She casts a sideways glance at me. “Don’t you like seeing all the holograms replaying last night’s game on the plaza? I know it’s kind of cheesy, but they’re fun to watch and walk through.”

“Let’s just go down Jasper Ave,” I say.

As we walk down Edmonton’s main street, we draw stares from the pedestrians around us. I feel the curious glances as people see my form flickering back and forth between two interpretations. A car races by, trying to pass another along the curb, and we dance back from the tsunami of slush its tires throw up onto the sidewalk.

Next to me, Diana pushes her sunglasses up her nose and lifts her head up higher. I see her subtly turning her head, noticing all the people who are watching us.

“For a while,” I tell her, “I was a reverse-pickpocket on the LRT. I spent all day slipping fifties into people’s pockets. That was near the beginning of my adventures.”

“How did you get the money?” she asks.

“It was leftover from a long-ago life I gave up so I could enjoy adventures like this. No more money, but now I have an abundance of time.”

“That is the privilege of wealth,” says Professor Tammy.

We pass a Second Cup, and a bunch of teenagers in the window stare out at us. A bus drives by, and several people do double takes at us we disrupt their lazy gazing out at the familiar street. We are bright sparks in a grey landscape.

“What life are you trying to leave behind?” I ask Diana, eager to change the subject.

She sighs and the rock-star aura imbued by her sunglasses fades a little.

“Every day after school I go to Arby’s and have a Beef ‘n Cheddar sandwich and read Wikipedia articles until my mom has gone home from work and gone out again. Then I get an Orange Julius and take the bus home and watch the game, or play Xbox. That’s my life.”

“But not today.”

“Today Brendan and his friends saw me in the food court.”

We turn off Jasper Avenue, start walking south to the bridge.

“They don’t like me because I’m smart and not pretty. Isn’t that dumb? If I were pretty, they would be intimidated by how smart I am and want to impress me. But they see my fat, and they shift inside from being impressed to being annoyed. ‘Oh,’ they think, ‘who does this fatty think she is? Why should I listen to her? What does she know about anything? She can’t even control herself enough to not stuff her fat face!’”

Diana’s face has gone red, and her voice catches.

“Well fuck ‘em,” I say. “I’m impressed. Not many people would be brave enough to come on an adventure like this. Most people are too prejudiced.”

We walk out to the middle of the bridge, where wind carried along by the river howls at us. Chunks of ice float downstream. The setting sun brushes long streaks of orange-gold pigment across their white canvasses. Soon the night chill will descend on Edmonton, and freeze it all over again.

“Maybe they’re right though,” says Diana as we lean against the rail and look out. “Maybe I am annoying. I do think I’m smarter than them, and I don’t try to hide it. I know I’m fat and ugly, and I won’t delude myself into thinking I’m not.”

She sighs and looks down at the river far below.

“Maybe I do belong here.”

She turns her blistering gaze on me, vaporizing the fairy godmother with a single arched eyebrow.

“Maybe when we pretend about ourselves, when we imagine fantastic things, we’re just avoiding the truth of our situations. And the truth is that this is an ugly city, full of worn-down, faded-out people.”

I open up my bag, take out a chunky gold ring I acquired recently.

“Or maybe it’s full of diamonds in the rough,” I say. “Of geodes waiting to be split open, unaware of the thousand glittering surfaces inside of themselves.” I take off one of her Team Canada mittens and slide the ring onto her finger. I can feel the heat radiating from her stout little body.

Just then some lights pop on down in the river valley. We all turn to look instinctively.

“Of course,” says Diana. Her arm lances out at the glowing building on the riverbank. “That’s it! There. That’s my revised wish.”

* * *

The Rossdale Tea Experience opened its doors only a few months ago, and has since endured a constant stream of cries to shut it down. An eccentric billionaire named Eugene Fulgens purchased the old Epcor Power Plant from the City of Edmonton, offering them a price they couldn’t refuse. To the frustration of his apparent heirs and to city planners eager to tear the building down, Eugene Fulgens bequeathed his entire fortune to a foundation which set up the Rossdale Tea Experience as his grandiose mausoleum.

Strung with strands of fairy lights and a million Christmas tree ornaments across the ceiling, the tea gardens are bathed in a warm, nostalgic glow. The lights snake out of the building’s windows, tangling across its roof and dripping down its sides, twisting up the abandoned smokestacks which knife the night sky. Depending on your point of view, the result is either a magical, whimsical bright-spot in an otherwise drab landscape, or a gaudy, light-polluting eyesore.

We arrive at the glowing building’s entrance to find a black-vested host with a woolly white moustache standing at a lectern.

“Good evening ma’am—er, excuse me, sir, er,” the host stumbles through titles, then grits his teeth and stops awkwardly. “Do you have a reservation?”

“No,” I say, “but we’d like to go in.”

He casts an appraising eye over us and arches an eyebrow.

“We have a dress code.”

“Ah!” I pat my bag. “That won’t be a problem. Just a minute.”

I toss down my bag and we dig through it again. I select a green vest with pearl buttons, perfect for emulating an English Earl. Professor Tammy shimmies into a tweed jacket which complements her bow-tie perfectly, and Diana takes off her mittens and bulky pink coat and slips on some white opera gloves.

“We’ll go through now, my good man,” I pat the host on the shoulder as we go past. “Keep my bag will you? There’s a good chap.” He nods deferentially. We walk inside, and Diana gasps.

When the power plant was decommissioned they demolished everything inside of the building, leaving only the outside shell standing. This demolition included all the plant’s floors, all the way down to the third sub-basement, which means that the giant room which now functions as the Rossdale Tea Experience extends some fifty metres below street level, down into the riverbank. Upon entering this massive space, one can’t help but feel awed.

We make our way down a red-carpeted spiral staircase to the tea gardens. At the bottom there is a sign: “Please remove your shoes and enjoy the grass between your toes.” The room’s floor is freshly turfed every week, and green grass covers it entirely. We slip off our shoes. The grass is magnificent after the long winter. Our feet were starved for its touch.

“Shall we take a table?” I ask. “It looks like we have our pick of the lot.”

The Tea Experience was the toast of the town, or at least a popular eccentricity, when it opened. Now they’re struggling to fill tables. Several scathing reviews by prominent food critics halted the flow of customers. The critics’ main concern was with the absurdity of serving high tea as a 24-hour buffet—making one of the most decadent and posh meals feel like a continental breakfast at some cheap motel. But most controversial is the tea feast’s centrepiece.

In the middle of the giant room, surrounded by white wooden chairs and garden-party tables set with flickering candles, the body of Eugene Fulgens lies in a crystal case. The buffet is spread around him—stacks of cakes and scones, bowls of clotted cream and honey, endless samovars of tea.

“I think we’re the only people here,” says Diana as she cranes her neck to look around the room. “Yep, I think it’s just us—oh wow…”

I follow her gaze and notice the far wall. “Woah.”

The destruction of all the floors didn’t prove a problem for the interior designers charged with creating the Rossdale Tea Experience to Eugene Fulgens’ specifications. They just built the spiral staircase down from the entrance to the ground floor. But when the city safety inspectors examined the superstructure, they discovered that the building’s gutting had significantly weakened the support for the riverside wall. Their objections were silenced with envelopes of cash, and the fancy tea gardens opened on schedule.

We walk up to the riverside wall. It has an enormous vertical crack down its centre, with tons of tiny cracks branching out from it. As per the wishes of Eugene Fulgens, there are thousands of pieces of paper stuck to this wall—prayers to the river, to maintain the integrity of this vast room and to bestow us with its blessing. This dubious engineering strategy seems fun, so we take some of the paper and pens from a nearby table, and contribute our own prayers to the wall.

Turning our backs on the wall proves surprisingly difficult, so we back away slowly before we continue to explore the room. We wend our way through the tables, confirming that we’re the Tea Experience’s only customers tonight. In the far corner, we discover another surprise: “Please Do Not Play On The Turbine Wreckage,” says a sign in front of some red velvet ropes, behind which a twisted pile of metal has been shoved into the corner. A giant gilded clockwork music-box sits beside the wreckage. I go over and wind it up, and a familiar waltz starts tinkling out into the room.

“Well,” I say, “Shall we get some tea?”

“I’m starving,” says Diana, then blushes. “I mean yeah, I could eat.”

We return to Eugene Fulgens and load up. We make several trips back and forth to a nearby table before we settle in to our tea feast. I’m about to take my first sip when I have a better idea: “A toast!” I raise my glass. “To Diana, new friend and adventuremate. I think I speak for Professor Tammy and myself when I say that this has been the best day ever.”

“SWITCH PLACES!” shouts Professor Tammy, and Diana and I both jump. “Huh huh huh,” she laughs huskily at us, and adds more almond milk to her tea.

I take a sip of my Earl Grey. I scarf down some baked goods and smile up at Diana. She hasn’t touched her food.

“What’s wrong?” I say through a mouthful of raspberry pie.

“It’s just, I’ve been waiting for the right moment… but I guess now is as good as ever.”

Diana pulls her maroon backpack out from under the table and sets it on the grass. She unzips it and takes out a thick navy blue binder with a familiar crest on the front, a teardrop of oil. She flips through pages and pages of laminated hockey cards, showing a panorama of all different sorts of men—some famous, most forgotten.

“My dad and I used to have season tickets. We wanted to collect all the players, every single one since the team was founded back in 1971. It was our special historical project.”

She flips to the back and slips a card out of its plastic sheaf. It’s signed.

“This is you, isn't it?”

A little man grins up at me, posed with his stick out in front of him.

“No. Not anymore.”

I run a grubby finger over the card’s glossy surface, smudging the little man’s face.

“No. It never was.”

I try to hand the card back to her but she won’t take it. I put it in my pocket.

“I knew it was you since I first saw you. I pretended I didn’t because you were pretending too. And I really liked you. You were our favourite. We liked you best because you proved everyone wrong. You weren’t big or strong. You weren’t what a hockey player is supposed to look like. But you were smart and quick, and held your own.”

Diana stares at me unflinchingly. I sigh.

“It’s true that I used to be part of a theatrical troupe called The Edmonton Oilers. Every night we’d put on performances—always the same show, but with some room for improvisation like any spectacle. We were well-received both locally and internationally. I remember putting on my costume and getting into character with my cast-mates before every show, waiting in the wings as the theatre darkened and the audience roared in anticipation, then rushing out onto the stage to begin the first act.”

I smile wearily at my two friends.

“It was fun, for a while. But I had to get out of there. ”

Diana stares at me unsympathetically. Accusatively.

“So you just left. Just like that.”

“I had to.”

“Why?”

“It was costing me too much to stay. I was destroying myself. Lopping off bits of myself. I needed something new.”

“I’ve lived a life that’s full,” says Professor Tammy. “I’ve travelled each and every highway.”

“But when you’ve committed to something, you need to stay with it,” says Diana, her face reddening, her voice quaking. “You can’t just run off. You can’t just disappear. That’s selfish. That’s cruel to the people you’re leaving behind. You’re just discarding them from your life like they’re garbage!”

She takes a long quivering breath. I can hear her heart pounding. I suddenly understand.

“He died, didn’t he? Your dad”

Diana looks down at her binder, talks into it.

“No. He moved. A month ago.”

“Oh. Phoenix.”

Diana blushes to the roots of her ginger hair.

“He left. Just left. Just went.”

She grabs her tea and shakily adds a spoonful of sugar to it. Her cup rattles in its saucer. I can still feel the sharp edges of the hockey card on my fingertips.

“So you knew who I was all along?”

She nods.

“You stayed with me today because you wanted to see what I would do?”

She nods again.

“Are you going to tell anyone?”

She stares into her tea for what feels like an hour, and eventually looks up at me. Her eyes are deep and sad. She shakes her head.

“Thank you.”

She shakes her head again.

“I just don’t understand,” she says. She rubs her eyes with the heels of her hands, and looks up at the Christmas-light-strung ceiling. “If someone like you can be so unhappy that you have to run away, what hope is there for the rest of us?”

“I don’t know,” I say.

We feast on in silence, but I’ve lost my appetite. After a while, I turn to Diana.

“The only thing I know is that today was a great day, and if I hadn’t left my old life I wouldn’t have been able to do any of it. You have to realize you’re starving before you can be bold enough to taste all the flavours of life. If you want to go to Phoenix, go to Phoenix. Sounds like the perfect place to start a new life.”

I see a flicker of hope in Diana’s eyes for just a moment.

“I can’t,” she says.

“Maybe not yet. But soon you must. Don’t starve yourself, Diana.”

Professor Tammy nods, speaks through a mouthful of cake:

“Life itself is the proper binge.”